The original Indiana Jones: Otto Rahn and the temple of doom

As Indiana Jones returns to our screens, John Preston looks at the Nazi archaeologist who inspired Spielberg's hero, and finds a story more bizarre than anything the director could have dreamt of

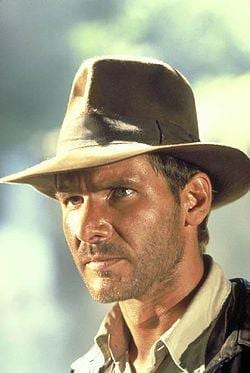

Very little is certain in the short life of Otto Rahn. But one of the few things one can with any confidence say about him is that he looked nothing like Harrison Ford. Yet Rahn, small and weasel-faced, with a hesitant, toothy smile and hair like a neatly contoured oil slick, undoubtedly served as inspiration for Ford's most famous role, Indiana Jones.

Like Jones, Rahn was an archaeologist, like him he fell foul of the Nazis and like him he was obsessed with finding the Holy Grail - the cup reputedly used to catch Christ's blood when he was crucified. But whereas Jones rode the Grail-train to box-office glory, Rahn's obsession ended up costing him his life.

However, Rahn is such a strange figure, and his story so bizarre, that simply seeing him as the unlikely progenitor of Indiana Jones is to do him a disservice. Here was a man who entered into a terrible Faustian pact: he was given every resource imaginable to realise his dream. There was just one catch: in return, he had to find something that - if it ever existed - had not been seen for almost 2,000 years.

What we can say for sure is that Rahn was born in 1904 and at an early age became fascinated with the Holy Grail. At university he was inspired by the example of another German archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann. Largely as a result of immersing himself in the Iliad, Schliemann had found what he believed to be the ruins of Troy on the western coast of Turkey.

Rahn decided that he was going to go one better: he would use the 13th-century epic Parsifal as his guide to finding the Holy Grail. Why did he think Parsifal would lead him to his goal? This is a tricky one - and, as with anything to do with the Holy Grail, one should never underestimate the power of wishful thinking.

But Rahn was also a serious scholar and the more he pored over Parsifal, the more he became convinced that the Cathars, the medieval Christian sect, held the secret to the Grail's whereabouts. In 1244, shortly before the Cathars were massacred by a Catholic crusade, three Cathar knights had apparently slipped over the wall of Montsegur Castle in the Languedoc area of France. With them, hidden in a hessian bag, was a cup reputed to be the Holy Grail.

Rahn arrived at Montsegur in the summer of 1931. He didn't find the Grail, but he did find a complex of caves nearby that the Cathars had used as a kind of subterranean cathedral. If he'd been of a less optimistic bent, he might have shrugged his narrow shoulders and gone home. Rahn, however, wasn't the going-home type. Certain he was on the right track, he wrote a book called Crusade Against the Grail in which he described his quest.

It was at this point that Rahn met his Mephistopheles. One day in 1933 he received a mysterious telegram offering him 1,000 reichsmarks a month to write the sequel to Crusade Against the Grail. The telegram was unsigned, but he was instructed to go to an address in Berlin - 7 Prinz Albrechtstrasse.

When he arrived, he was understandably surprised to be greeted by the grinning figure of Heinrich Himmler, the head of Hitler's SS. Not only had Himmler read Crusade Against the Grail; he'd virtually committed the thing to memory. For the first time in his life Rahn met someone even more obsessed with finding the Grail than he was. Indeed, so confident was Himmler of finding the Grail that he'd already prepared a castle - Wewelsburg in Westphalia - for its arrival. In the basement, surrounded by busts of prominent Nazis, was an empty plinth where the Grail would go.

All Rahn had to do was find it. He seems to have been blithely unaware of what he was letting himself in for. Initially, Rahn saw no reason to join the SS, but when it was intimated to him that Himmler would be pleased if he did, he duly signed up. A few weeks later a friend ran into him wearing the black uniform of an SS Sturmbannführer and asked him what on earth he was doing.

'A man has to eat,' Rahn replied sheepishly. 'What was I supposed to do? Turn Himmler down?'

Rahn now had the full backing of the SS. But he also had no excuse not to come up with the goods. He wrote another book, with the none too catchy title of Lucifer's Court: A Heretic's Journey in Search of the Light Bringers, which detailed his further efforts to find the Grail.

Perhaps it's too much to expect a professional Grail-hunter to have a fancy prose style. Even so, his books read as if he were encased in heavy armour while he was writing them. 'Look, I will tell you a secret,' he wrote in Lucifer's Court. 'The time has come for the groom to crown his bride; guess where the crown lies. Towards midnight, because the light is clear in the darkness.'

There was more in a similar vein - a lot more. To the untrained ear, this has a note of desperate flannel about it. However, Himmler loved the book and ordered 5,000 copies to be bound in the finest leather and distributed to the Nazi elite. By now it must have dawned on Rahn that he was swimming with some extremely nasty sharks. It must also have dawned on him that he was trapped - especially when he read the proofs of Lucifer's Court and found that one blatantly anti-Semitic passage had been inserted by someone else.

According to Jeremy Morgan, whose uncle, Herman Kirchmeir, was a friend of Rahn's, the two men shared an interest in Parsifal and the Grail. 'They used to go climbing together, exploring caves and so forth. I used to hear about him as a child. The feeling in my family was that Rahn was an honourable man who had got himself into this terrible bind. He wasn't anti-Semitic, but he'd taken the SS's money because he needed funding for his archaeological projects. Then, having done so, he couldn't get out.'

What gives Rahn's dilemma peculiar piquancy is that there's evidence to suggest that he was Jewish himself - although it's not clear if he was aware of it. He was also gay. Bravely, if naively, Rahn began to move in anti-Nazi circles. Nigel Graddon, author of a new biography of Rahn, Otto Rahn and the Quest for the Holy Grail: the Amazing Life of the Real Indiana Jones, believes that Himmler's disenchantment with Rahn was a result of his failure to find the Grail.

'Basically, he came back empty-handed,' he says. 'That was his biggest offence. It's true that Rahn did voice anti-Nazi sentiments, but he was always pretty discreet about it. What would have been far more of a problem to Himmler was that Rahn was openly homosexual. In the early days, Himmler had been prepared to turn a blind eye to it. But as time went on, his tolerance wore thin.'

In 1937, Rahn was punished for a drunken homosexual scrape by being assigned to a three-month tour of duty as a guard at Dachau concentration camp. What he saw there appalled him. Clearly in a state of anguish he wrote to a friend, 'I have much sorrow in my country… impossible for a tolerant, liberal man like me to live in a nation that my native country has become.'

He also wrote to Himmler resigning from the SS. This, too, was as naive as it was brave - the SS being the sort of organisation you only resigned from feet-first. Although Himmler accepted Rahn's resignation, he had no intention of letting him escape. What happened next is unclear. There are stories that Rahn was threatened with having his homosexuality exposed, also that he had links with British Intelligence.

Told that SS hitmen were out to get him, Rahn was apparently offered the option of committing suicide. One evening in March 1939, he climbed up a snow-covered slope in the Tyrol mountains and lay down to die. He is believed to have swallowed poison, although no cause of death was ever given. The following day Rahn's body was found, frozen solid. He was 34.

'I always understood that he had chosen his favourite spot to die in,' says Morgan. 'He was lying down looking up at the mountains, rather as if this might lead his soul to some Arthurian heaven.'

And there the story might have ended - except that Hollywood has conferred a strange kind of immortality on Otto Rahn. But it's not only Hollywood; on the internet, his memory continues to be bathed in a richly speculative glow, fanned by ever more outlandish theories about his fate.

Predictably, there are stories that Rahn was murdered, or that he didn't die at all in the Tyrol - this was just a clever bluff to fool the Nazis. Instead, he apparently survived, changed his first name to Rudolf and went on to become the German ambassador in Italy. Graddon believes that, 'There is too much fog swirling around his headstone. We simply don't know what happened to him, and as a result all kinds of rumours have sprung up.'

As for the Grail, that too lives on, with claimants and contenders continuing to turn up in the most unlikely places. The most recent sighting was in 2004 when it was supposed to have been found in the late Lord Lichfield's back-garden in Staffordshire. As the estate manager said at the time, 'The Grail is like Everest: you climb it because it's there.' Or not there, of course.

John Preston, 22 May 2008

- Inicie sesión o regístrese para enviar comentarios

Similar By Terms

|

(Deutsch)

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

(Español)

|

(English)

|

Comentarios recientes

hace 13 años 50 semanas

hace 13 años 50 semanas

hace 13 años 50 semanas

hace 13 años 51 semanas

hace 14 años 2 semanas

hace 14 años 7 semanas