Rennes-le-Chateau

Here, on the northern edge of the Pyrenees some 110 years ago, a Catholic priest named Bérengier Saunière became unbelievably wealthy overnight, seemingly after discovering something of immense value or significance in his church. He is said to have spent lavishly redesigning the tiny hill-top structure, building a strange belvedere tower called Tour Magdala and constructing a guest house known as Villa Bethania. He is also reported to have started acting oddly, erasing inscriptions on tomb stones, carrying out nocturnal excavations in both the church and churchyard, and receiving visitors totally beyond his standing as a parish curé in a rural part of southern France.

No one knows what Saunière might have stumbled upon, but it was either a commodity, such as gold or treasure (many rumours existed in the area concerning lost treasure), or a great secret which he was handsomely paid to keep quiet about by an unknown paymaster. Another strong rumour preserved locally indicates that shortly after his discovery he spent time in Paris where he met with various individuals including priests of the seminary of Saint Sulpice, who directed him to obtain copies of paintings hanging in the Louvre art gallery. One of these was a masterpiece by seventeenth-century French artist Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665) entitled Les Bergers d'Arcadie (‘The Shepherds of Arcadia’), which shows a group of shepherds and a shepherdess looking at a stone tomb perched on the edge of a rocky landscape. Their eyes gaze in bewilderment at a Latin inscription carved into its side which reads ET IN ARCADIA EGO, ‘Also in Arcadia I’, or ‘And I too (am) in Arcadia’, interpreted by art historians as meaning even in Arcadia, the earthly paradise in Greek mythology, where the great god Pan presides, death can be found.

The strange thing is that a stone tomb matching the description of the one seen in Poussin’s painting was, until its destruction in the late 1980s, to be seen perched on a rocky outcrop overlooking a mountain valley outside the town of Arques, close to Rennes-le-Chateau. Obviously, this has suggested to the inquisitive that Poussin might have visited the area on his travels and decided to paint the view, using the tomb as a central focus. Unfortunately, however, the tomb in question dated back only to the beginning of the twentieth century, and yet local tradition asserts that it replaced an earlier example on the same spot. Moreover, Poussin is not known to have visited the Aude region, where Rennes-le-Chateau is situated, thus any similarities between the painting and the Tomb of Arques, as it is known, should be purely coincidental.

Somehow, Bérengier Saunière would appear to have been aware of this conundrum, hence his purchase of a copy of the painting when in Paris. And if this is true, then he might also have known that the line of hills shown in the background of the painting seem to feature three prominent local landmarks as viewed from the tomb’s elevated position - a peak called Pech Cardou, a promontory with a ruined tower named Blanchefort, and, on the right-hand edge of the picture, the hill on which Rennes-le-Chateau stands.

Was there some clue to the mystery of Rennes-le-Chateau being offered by Poussin’s painting, and was Saunière aware of some hidden tradition which revealed an occult secret of immense importance? These have been the primary questions asked by historical writers since the 1960s, the most famous being the trio of British authors who put together the masterpiece of publishing we know as THE HOLY BLOOD AND THE HOLY GRAIL, which appeared originally in 1982. Written by television presenter Henry Lincoln, writer and historian Michael Baigent and historical researcher Richard Leigh, it became a worldwide bestseller and attempted to answer the riddle of Rennes-le-Chateau. It sought to unravel the mystery in terms of an underground stream of knowledge regarding a royal bloodline, the sangreal, the ‘blood royal’, created from the marriage of Jesus Christ to Mary Magdalene, who in medieval legend was said to have ended her days in France. From this royal line emerged the Frankish dynasty of kings known as the Merovingians, the most famous being Clovis I, who reigned c. AD 500. He was crowned ruler of the Frankish empire by the bishop, or ‘pope’, of the fledgling Catholic Church, which proclaimed the dynasty’s royal blood as divine. However, when the Merovingians began losing their grip on the empire in the late seventh, early eighth centuries, they were ousted in favour of their mayors of the palace, a hereditary family who ruled as the Carolingians, the most famous of whom was Charles the Great, or Charlemagne, who reigned c. AD 800. He was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope, although unlike the blood of the Merovingians that of the Carolingian kings only became holy through anointment at the time of their coronation, a ritual act which Israelite kings underwent in order to bestow on them the power and protection of Yahweh.

According to peculiar documents produced by a French secret society founded in June 1956, the heirs of the Merovingian royal family made attempts to reclaim the Frankish throne and were supported in their cause by a clandestine organisation from which they themselves took their name. Known as the Prieure du Sion (‘Priory of Sion’), its purpose has been to keep alive Merovingian aspirations and hopes through to the modern day, and in its time the organisation has involved some of the most illustrious names in history. It is a story involving the treasure of the Cathar heretics, the Knights Templar, the Rosicrucians, various secret orders down through the ages, and, inevitably, the mystery surrounding Rennes-le-Chateau, which in the age of the Merovingian kings was an important city called Rhedae.

According to the Prieure documents, it was to here that Sigisbert, the son of Dagobert II, the last king of the Merovingian dynasty, was secretly carried to safety following his father’s assassination on a hunting expedition, an event thought to be commemorated on a stone plaque found face downwards by Sauniere when removing flagstones from the area in front of the altar in Rennes-le-Chateau’s church. Known today as the Knight’s Stone, some believe it to show the young child being carried by a knight on a horse, an opinion not shared by French historians.

In the early twentieth century certain Cathar apologists came to believe that German Minnesinger and poet Wolfram von Eschenbach, when referring to Munsalvaesche, the Grail castle, in his classic work Parzival, written c. 1210-1220, had been alluding to the mountain fortress of Montsegur, where 200 Cathars were massacred in 1244, an atrocity which brought to a close the so-called Albigensian Crusade against such heretics. The matter was taken up during the late 1920s by German historian and author Otto Rahn (1904-1938), who would go on to become a personal friend of Nazi SS leader Heinrich Himmler and join the SS himself in 1936. He arrived at Montsegur in search of the Grail, firmly believing it to have been carried to safety shortly before its fall. For him it was a simple cup fashioned from an emerald-green stone plucked by the archangel Michael from Lucifer’s crown at the time of the wars in heaven. Yet later claims that Rahn found the Grail and presented it to Himmler, who placed it on display at the castle of Wewelsburg, the Nazi Munsalvaesche, are unfounded.

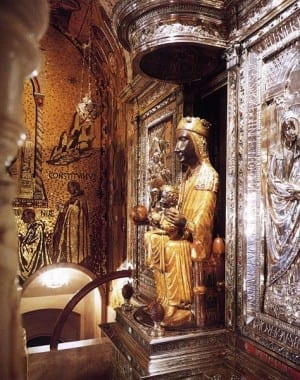

So what then was Rennes-le-Chateau’s own role in the Grail mystery? Although there might be sound historical foundations to the theories outlined in Holy Blood, Holy Grail , which sees the Holy Grail as the sangreal, or ‘blood royal’, quite literally the bloodline of Christ, this is by no means the solution to the mystery which has continued to baffle researchers to this day. Some believe that the various references to the importance of the Magdalene in the village (i.e. the church’s dedication to the Magdalene, Sauniere’s Tour Magdala; his Villa Bethania, honouring Mary of Bethany, long considered to have been another name for the Magdalene, and a nearby Magdalene cave grotto), suggest that she is buried there. Yet there is no hard evidence that any legend surrounding her ending her days in France existed prior to 1050, and even less to support the view that her remains might have found their way to Rennes-le-Chateau.

Henry Lincoln has proposed in his own books that the key to the mystery is knowledge of pentagonal geometry laid out across the landscape around Rennes-le-Chateau; the pentagram being the design that the planet Venus makes in the sky during its roughly eight-year cycle as viewed from the earth. Since Mary Magdalene might be equated with Venus in its personification as the goddess of love, fertility and sexual rapture, then perhaps this sacred ground-plan was the secret found by Saunière. The problem with this theory is that Henry Lincoln’s geometry is so vast and complicated that it is unlikely to have been known to a simple parish priest. More likely is that Saunière came across two treasures - one material, perhaps gold coins from the Merovingian, Visigothic or Roman periods, and the other non-material, a secret which he kept quiet about during his life, telling only his house keeper and constant companion Marie Dénarnaud, and seemingly one or two of his priest friends.

- Vous devez vous identifier ou créer un compte pour écrire des commentaires

Termes similaires

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

(English)

|

Commentaires récents

il y a 13 années 50 semaines

il y a 13 années 50 semaines

il y a 13 années 50 semaines

il y a 13 années 51 semaines

il y a 14 années 2 semaines

il y a 14 années 7 semaines